When it comes to plants that I seem destined never to acquire, the koshiabura tree Chengiopanax sciadophylloides is surely at the top of the list. This small tree in the ginseng family Araliaceae is an endemic Japanese species which is revered as a spring vegetable. Koshiabura grows along the full length of Japan from the mountains of Hokkaido to Kyushu in the south. It likes to grow along sunny woodland edges on mountain slopes.

Wild vegetables in Japan are referred to as “sansai”, which translates literally as “mountain vegetables”. The koshiabura tree is so revered as a wild food in Japan that it has earned itself the title of “queen of sansai”. (The “king of sansai” is the closely related Aralia elata) The young shoots of the koshiabura tree are harvested in the spring and are boiled to serve in a variety of dishes, or fried up raw as vegetable tempura. They are grown commercially on a small scale and can even be found in Japanese grocery stores when in season. It is said that koshiabura trees growing along mountain paths are often stunted due to excessive harvesting of the shoots!

The young shoots of many trees and shrubs in the ginseng family Araliaceae are eaten as sansai in Japan. These include Aralia elata, Kalopanax septemlobus, a few Eleutherococcus species, Gamblea innovans, and finally Chengiopanax sciadophylloides. There are two attributes which make koshiabura especially desirable among this group. First of all, unlike most of the other species, which are viciously thorny, koshiabura is completely free of thorns. Second, the plant has a milder flavor than most other Araliaceae species, free of the harsh bitterness found in some of the species listed above. In a 2004 paper, David Brussell, an American ecology professor living in Japan, stated that koshiabura shoots were his favorite of the many sansai he tried during his stay, describing them as “delicious”.

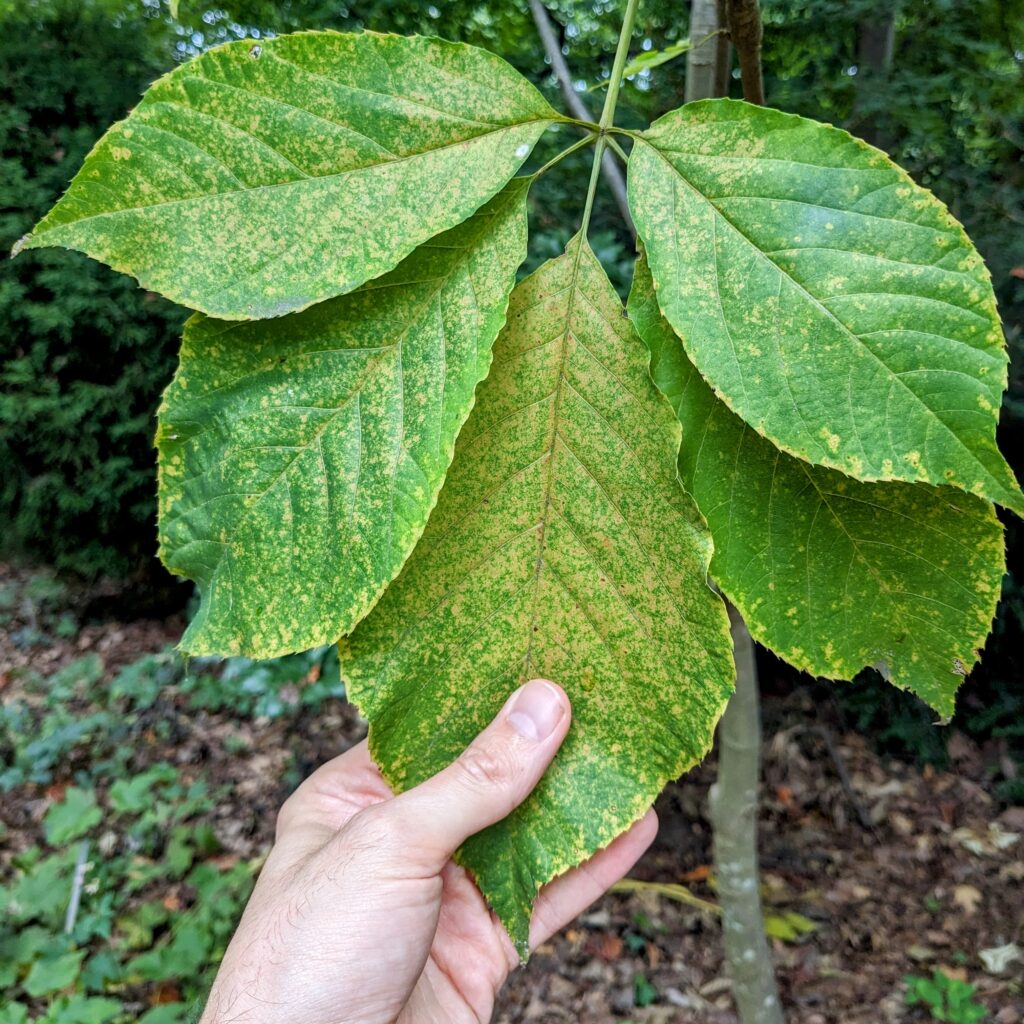

Of course, I can’t personally comment on the flavor of the plant, as I’ve been completely unable to source one! As far as I know, the only koshiabura tree growing in the United States at present is a single small specimen growing in the Asian Collections at the US National Arboretum in Washington, DC. Unfortunately the species is dioecious, with separate male and female plants, so the tree in Washington DC will never produce seed for further propagation. Readers in the UK can get this plant from Crûg Farm in Wales. As for the rest of us, we’ll have to import seeds or plants directly from Japan – a difficult process any way you look at it. Some research has shown that the koshiabura tree can accumulate manganese from the soil into its leaves, potentially reaching hazardous levels. Sometimes I’ll use this fact to make myself feel better about not being able to obtain this plant!

The name “koshiabura” might sound odd to English speakers, but the tree has no English common name as it is only found in Japan. “Koshiabura” translates to “strained oil” in Japanese – a reference to one of the historical uses of the tree. By straining the resin found in the tree, a prized lacquer called “gonzetsu” is obtained. This lacquer was famous among Japanese and Chinese nobility for its glossy golden color and high durability, actually becoming harder when exposed to ultraviolet light. Koshiabura and the closely related Gamblea innovans were used for this purpose until the Heian period (794 to 1185 CE) when it was discovered that the faster-growing Toxicodendron vernicifluum could be used instead.

There are a lot of unknowns when it comes to the koshiabura tree. How large will it grow outside of its native range? Japanese sources list it as growing from 5 to 18 meters tall. What are its actual hardiness limits? The Arnold Arboretum in Boston, Massachusetts has attempted to grow it several times, but none of the trees have survived to the present. There is also a Chinese species, Chengiopanax fargesii, which is even more obscure but is likely to have all of the same useful properties. I hope to one day grow one of these obscure edible trees in my own garden so that I can answer some of these questions for myself! If you are able to get your hands on this species, by all means please let me know!