I had the great pleasure of visiting the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew in London during my recent trip to the UK. I’ve compiled a collection of photos I took there showing my favorite hardy (and some not so hardy) edible plants. Descriptions are below each set of photos. You can click the individual photos to see the full-sized versions. Enjoy!

A magnificent old specimen of servicetree, Sorbus/Cormus domestica. This is a rare European tree which produces an abundance of small delicious fruits in the fall. The fruits look like tiny apples or pears, and must be eaten overripe or “bletted”. They taste like apple or pear sauce, but with complex tropical fruit flavors as well. I think this tree has incredible potential in agroforestry systems because its pinnate foliage lets plenty of light through to the understory. The fruit is easy to harvest despite the large size of the tree because it falls freely when ripe. The main downside of growing this tree is that it can take several years to begin fruiting!

The incredible gray-white bark of this tree caught my eye from a distance, so I had to investigate! Upon looking closer, I realized that it’s actually one of my favorite trees with edible leaves – Staphylea holocarpa var. rosea, a pink-flowered form of Chinese bladdernut. You can read my full write-up about the bladdernuts here for more information about the many species and their edible uses. Note the pink-tinged seedpods characteristic of this variety in the last two photos. As far as I’m concerned this is easily the most ornamental of the bladdernuts!

A beautiful old medlar tree, Mespilus germanica, planted in 1935. The medlar is a close relative of the hawthorns in the genus Crataegus. It produces an unusual fruit in the fall with a large open calyx on one end. The fruits must be eaten when overripe or “bletted” and when perfectly ripe taste like spiced apple sauce. In my garden the best time to harvest them is between Thanksgiving and Christmas, when few other fruits are available. The large white flowers and long fuzzy leaves lend an aristocratic look to this uncommon fruiting tree.

A large Chinese toon tree, Toona sinensis, planted in 1959. This tree is revered in China for its edible young leaves, which taste of vegetable stock or beef and onions. These trees tend to sucker a lot in the Eastern United States, but this one had only a few small suckers around the base. It’s possible that the garden staff removes them judiciously. Note the pinkish hue of the young leaves at right.

The captivating exfoliating bark of a Chinese quince tree, Pseudocydonia sinensis. This is a relative of the true quince, Cydonia oblonga, that produces even larger fruits! Chinese quince fruits can be up to 7 inches long and 5 inches wide, and are exceptionally fragrant. They are a bit harder than the fruits of true quince, but can be used in all the same ways. The Chinese quince has attractive pink flowers in the spring, but its main claim to fame is the incredible multicolored peeling bark. This tree is hardy to zone 6b, but can suffer from fireblight in warmer and wetter climates.

The delicate white flowers of Bumald’s bladdernut, Staphylea bumalda, growing in a shaded area near the redwood grove. This 6 foot (2 m) shrub native to China, Korea, and Japan, has delicious flowerbuds and young leaves. It is the main subject of my bladdernut article. It’s called “tree cauliflower” in parts of China!

Yellowhorn, Xanthoceras sorbifolium, is an unusual small nut tree from China with beautiful flowers and pinnate leaves. This is by far the largest yellowhorn tree I’ve ever seen, planted in 1977. The nuts, which form in a funky pod resembling an ackee fruit (to which it is related), are edible but bitter. Traditionally the nuts are pressed to produce a cooking oil. This tree is adaptable and easy to grow and its small size makes it easier to manage than larger nut trees. It could be a great way to produce cooking oil in small spaces or areas with soil too poor for other species to grow.

The unusual flowers and blue-tinged stems of the blue bean tree, Decaisnea fargesii. This is a shrubby relative of Akebia from China, that is uncommon in cultivation. The tree is mainly known for the bright blue pods it produces in the fall, which have earned it the moniker “dead man’s fingers”. In my climate the pods ripen on Halloween every year – how fitting. The blue pods are edible and contain a sweet-flavored pulp and countless hard inedible seeds. Although there is little pulp to be had in each pod, this tree has a long history of edible use in rural China.

The entire property was littered with massive specimens of Castanea sativa, the European sweet chestnut – truly a sight to behold! As an American it really drives home how incredible the American chestnuts (Castanea dentata) of the East Coast must have been before they were wiped out by the chestnut blight. Castanea sativa prefers a milder climate and does best in places like Italy and California. Hybrid chestnuts have been developed which perform much better in colder areas.

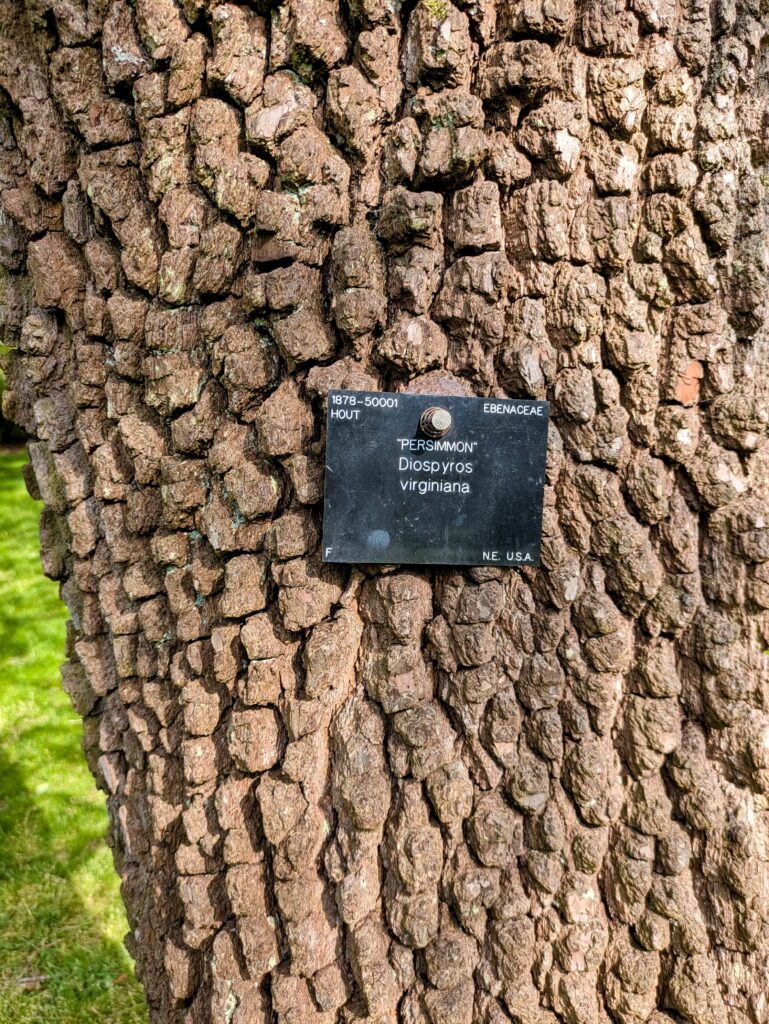

This tree, planted in 1878, is the largest American persimmon, Diospyros virginiana, in the UK. Kew has a nice grove of persimmon trees, which mainly consists of Diospyros lotus, the date-plum, but with a handful of American and Asian persimmons (Diospyros kaki) as well. All of the persimmons produce edible fruits, though they vary in size, texture, and flavor. Persimmons are one of the easiest fruits to grow in any area where there is enough summer heat for them to ripen.

The monkey puzzle tree, Araucaria aracuana, is an endangered conifer from Chile, where it grows in dramatic fashion on high mountain slopes. One of the most striking trees to behold, the individual leaves are stiff and sharp, apparently an ancient adaptation to prevent dinosaurs from eating them. While this tree is hardy down to USDA zone 6, it prefers areas with milder winters and cooler summers such as the UK and Pacific Northwest of the United States. The trees are dioecious, and female trees produce large seedpods containing starchy edible nuts. In the photo on the left you can see a female tree to the left and a male tree to the right. The female tree has large rounded cones at the top of the tree, and the male tree has smaller but showier cones dangling from the tips of each branch.

Kew Gardens has an impressive collection of plum-yews, a group of East Asian conifers in the genus Cephalotaxus. While they are related to the true yews in the genus Taxus, plum-yews produce a much larger fruit and are significantly less toxic overall, attracting the attention of some novel fruit growers. The fruits (actually a fleshy seed aril, but I digress) have a unique flavor which I would liken to lychee with a hint of persimmon and pine sap. The photos above show the attractive reddish bark and young fruits forming on a specimen of Cephalotaxus harringtonia, the Japanese plum-yew. The big obstacle to growing plum-yews for their fruits is that they are dioecious and typically take at least 5 years to begin producing cones. This means you have to grow a handful of seedlings out for 5 years or more in order to get fruits. Still, there is some merit to growing plum-yews, as they can fruit in nearly full shade and make a nice evergreen hedge once established.

A mature che tree, Cudrania/Maclura tricuspidata, planted in 1973. This is an uncommon fruit tree from East Asia which produces red fruits in fall that look like little brains. The fruits are juicy and have a watermelon-like flavor. Trees are dioecious, but female trees will produce seedless fruit if no male tree is present. The fruits have just enough time to ripen before the first frost in my zone 6b garden – they require summer heat. This species is typically grafted on osage orange (Maclura pomifera) rootstock to prevent suckering.

A nice specimen of Eleutherococcus trifoliatus, a climbing eleuthero species from Southeast Asia, where the leaves and shoots are eaten as a vegetable. I tasted a small leaf and was surprised by its good flavor – parsley-like and free of bitterness. This plant was growing in the temperate house, which contains temperate plants that prefer warmer conditions. I’m unsure how cold-hardy this species actually is, though most Eleutherococcus species are very hardy. This species is very rare in cultivation but has become invasive in parts of Florida.

The Araliaceae collection was in poor shape overall but did offer a look at some uncommon species in one of my favorite plant families. All of the species here have edible young leaves and shoots, eaten throughout East Asia. At top left is Kalopanax septemlobus, the castor aralia – a large tree with vicious thorns and unique palmate leaves. This specimen had died to the ground (note the giant stump), but was resprouting vigorously. At top right is an unlabeled Aralia species – likely Aralia elata or one of its close relatives – a suckering thorny shrub or small tree with attractive bipinnate foliage. While these plants are generally incredibly thorny, they can become thornless with age as seen here – an adaptation to prevent deer browsing of young plants. At bottom left is udo, Aralia cordata, an excellent perennial vegetable widely utilized throughout East Asia. Despite being an herbaceous perennial, it can become so large that you would think it was a shrub! And finally at bottom right is Eleutherococcus simonii, a rare shrubby species from China with unusual fuzzy leaves. I recently learned that a purple-leaved variety of this species is grown for edible and medicinal use in Yunnan province.

An old specimen of Cornus mas ‘Aurea’, a variety of cornelian cherry with bright yellow new growth. It was even more striking to see in person! This tree must have been propagated from a cutting, as a grafted tree would not be able to have such a multi-stemmed form. Cornelian cherries are one of the easiest fruiting trees to grow, producing large amounts of small red fruits with a sweet-tart flavor in late summer. I recommend growing improved fruiting varieties such as ‘Elegant’ and ‘Yellow’ – just be sure to plant more than one for cross-pollination.

Castanea henryi, or Chinese chinquapin, is a rare Chinese species of chestnut that produces tiny edible nuts. This species has attracted attention from chestnut breeders for its complete immunity to chestnut gall wasp, a scourge of many chestnut orchards. By crossing this species with chestnuts that produce larger nuts, the hope is to create a delicious large chestnut that isn’t affected by chestnut gall wasp. This tree, while small, is actually very old – planted in 1913. It has developed an interesting pendulous habit that I’ve seen in other old specimens of Castanea henryi.

A couple of specimens of Hovenia dulcis, the Japanese raisin tree. This large tree in the buckthorn family Rhamnaceae produces one of the most unusual edible fruits you’ll ever see – because it’s not a fruit at all! The fruit stalk or peduncle becomes fleshy and sweet, with a date-like flavor. When dried, these “fruits” can be used similarly to raisins, hence the name. This tree is adaptable to an incredible range of climates – it’s an invasive plant in the Brazillian rainforest, but I’ve also seen it thriving in Boston, Massachusetts. Older specimens develop bark which peels away in rectangular segments, revealing a reddish interior.

An impressive patch of Gunnera × cryptica, a hybrid of Brazilian giant rhubarb (Gunnera manicata) and Chilean rhubarb (Gunnera tinctoria). These water-loving plants are common in the UK, where they’re grown as an ornamental on the banks of ponds and streams. The plant was named “giant rhubarb” due to its superficial resemblance to true rhubarb (Rheum species) and its edible stalks, which have a long history of use in Chile. Unfortunately this plant is not terribly cold-hardy!

A couple of edible ornamental vines grown against a brick wall – at left is Schisandra sphenanthera, a rare species of Chinese magnolia vine with attractive red flowers, and at right is a male specimen of Actinidia kolomikta, arctic kiwi. The berries of Schisandra species are edible and medicinal, with Schisandra chinensis being the species most commonly grown. (Look for the self-fertile variety ‘Eastern Prince’) The berries of Actinidia kolomikta are a true dessert quality fruit, and are becoming more popular, now sold in supermarkets as “kiwi berries”. Male arctic kiwis typically showcase this incredible variegation, starting white and fading to shades of pink. The tip of each individual leaf appears to be dipped in pink paint!

The flowers and young fruits of Poncirus/Citrus trifoliata, the trifoliate orange – the hardiest citrus plant in the world, and the flowers and foliage of Berberis darwinii, Darwin’s barberry, an evergreen barberry species with showy flowers and tasty edible fruits. While intensely thorny, the trifoliate orange is an excellent novelty plant for northern gardens. It is hardy to at least zone 6. The fruits are seedy and bitter, but can still be used to make a nice marmalade. Darwin’s barberry, aside from its beauty and interesting history (discovered by Charles Darwin in Chile during his famous voyage onboard the Beagle) is also said to be one of the best tasting barberries. It prefers milder climates.

At left is sea kale (Crambe maritima) in bloom with a few Good King Henry (Chenopodium bonus-henricus) plants behind it. I was lucky to visit the UK during peak sea kale bloom. Each sea kale plant forms a beautiful mass of fragrant white flowers that are also edible and delicious – does it get any better? At right is the gorgeous pale blue foliage of cardoon (Cynara cardunculus) with rhubarb and forcing pots behind. Cardoon can struggle in cold winter climates, but is worth trying for its incredible foliage effect. Good King Henry, sea kale, and cardoon, all have edible leaves and shoots. Sea kale flowerbuds, which look like tiny broccolis, are one of the finest gourmet vegetables on Earth.

Two uncommon Asian raspberry species. At left is Rubus tricolor, an evergreen groundcover raspberry from Taiwan with fuzzy red stems and small orange fruits. It prefers a milder climate but makes an excellent groundcover where it does well. At right is Rubus crataegifolius – an attractive raspberry with large palmate foliage and showy white flowers. This species is thorny and aggressive but produces larger red raspberries – there are named fruiting varieties of Rubus crataegifolius in Korea.

Turkish rocket (Bunias orientalis) is gorgeous in bloom and the flowers are loved by hoverflies, a large class of beneficial insects – just don’t let it set seed or it’ll take over! The young leaves and especially the young flower buds are tasty on this species with a strong mustard flavor. Just about the easiest perennial vegetable you could grow. At right is a young sansho pepper tree, Zanthoxylum piperitum ‘Devon’. I wasn’t aware of any named cultivars of this species, so it was interesting to see this one. Sansho is popular among Japanese foragers, who harvest the spicy young leaves in spring. The main crop however, is the reddish seed husks in the fall, which, when dried and ground, are a world-class spice with a unique musky citrus flavor.

Two moisture-loving vegetables from East Asia – note the irrigation hoses! At left is Oenanthe javanica ‘Flamingo’ – the variegated version of water celery, a great albeit aggressive perennial celery plant. It never develops a large stalk like true celery, but the celery-flavored foliage and thin stems are a great addition to any dish. It’s also a beautiful groundcover with its attractive tricolor foliage! At right is the true wasabi plant, Eutrema japonicum, which has a reputation for being very difficult to grow outside of its native range. It grows naturally along wooded mountain streams in Japan, so that tells you the sort of conditions it likes. Most wasabi sold outside of Japan is actually horseradish root, Armoracia rusticana.

Leave a Reply